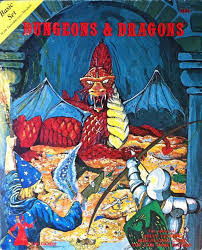

Holmes Basic Set (1977)

The blue box of the 1977 Holmes Basic Set introduced me to D&D. To ninty-nine percent of Dungeons & Dragons players, the edition that introduced them to the game stands as their most important. Why should I be different?

Players who came later never saw how revolutionary the game and its brand of fantasy seemed in the 70s.

Players who came later never saw how revolutionary the game and its brand of fantasy seemed in the 70s.

Then, games sold as toys and they were all terrible. They suffered from stupid, and random mechanics: Roll a die and move that many spaces. These games offered minimal choices. In them, the winner became obvious well before the end, yet they took forever to finish.

Before I saw D&D, I heard of the game in a 12-year-old’s lunch-room pitch. After school, I sat with a sheet of graph paper and tried to imagine how the game would play. I got nowhere. From my experience rolling a die and moving that many squares, I had no clue how a game could allow the things the kids claimed.

So in a mere 48 pages, the 1978 basic Dungeons & Dragons rule book edited by J. Eric Holmes shattered my notion of what a game could be.

As a kid in the 70s, All the fantasy I knew came from picture books. Stories where trolls lived under bridges and bugbears under beds. Nothing prepared me for a game inspired by Appendix N.

For more, see “4 popular beliefs Dungeons & Dragons defied in the 70s.”

City State of the Invincible Overlord (1977)

When I discovered D&D, TSR had yet to publish any setting information other than the hints published in the Grayhawk and Blackmoor supplements. For a break from dungeon adventures, the original rules suggested wandering the hex map packed in Avalon Hill’s Outdoor Survival game and rolling encounters.

So when the City State of the Invincible Overlord reached me, the scope of my game exploded. The $9 setting included a huge 34″ x 44″ map in four sections, and 11″ x 17″ map of the castle of the dwarven king backed with a sprawling dungeon map, three booklets detailing over 300 individual locations and the non-player characters who populate them, maps for ten more dungeon levels, plus players’ maps.

So when the City State of the Invincible Overlord reached me, the scope of my game exploded. The $9 setting included a huge 34″ x 44″ map in four sections, and 11″ x 17″ map of the castle of the dwarven king backed with a sprawling dungeon map, three booklets detailing over 300 individual locations and the non-player characters who populate them, maps for ten more dungeon levels, plus players’ maps.

The package shows remarkable creative output. No locations in the sprawling city rate as too mundane for descriptions. Even with five bakers, the guide finds something interesting to say about each.

Instead of adopting the entire City State, I cherry picked stuff I liked. My 1977 copy of the city state still contains the pencil marks noting my favorite bits. The best inspiration came from the rumors seeding every location. Now we would call them adventure hooks. In an era when most players just wandered, these ideas suggested a way to steer the game from aimless looting to plot.

For more, see “A butcher, a baker, and naughty nannies in the City State of the Invincible Overlord.”

Arduin (1977).

Inspired by the Greyhawk and Blackmoor supplements, Dave Hargrave printed his house rules, lore, and advice in 3 little, brown books named after his world, The pages of the Arduin Grimoire teemed with fresh ideas. When I discovered the books, I became enchanted. I haven’t found a game book that proved as enjoyable to read.

In an era when state-of-the-art setting design consisted of a map paired with encounter tables, Hargrave opened a world with detail that rivaled any setting that came later.

Dave Hargrave’s campaign world of Arduin was not built; it was piled. To create Arduin, Hargrave took every fantastic element he dreamed up or fancied and piled them into one work of love. He preached bigger imaginary playgrounds. “The very essence of fantasy gaming is its total lack of limitation on the scope of play, both in its content and in its appeal to people of all ages, races, occupations or whatever,” He wrote. “So don’t limit the game by excluding aliens or any other type of character or monster. If they don’t fit what you feel is what the game is all about, don’t just say ‘NO!,’ whittle on them a bit until they do fit.” (Vol. II, p.99)

Dave Hargrave’s campaign world of Arduin was not built; it was piled. To create Arduin, Hargrave took every fantastic element he dreamed up or fancied and piled them into one work of love. He preached bigger imaginary playgrounds. “The very essence of fantasy gaming is its total lack of limitation on the scope of play, both in its content and in its appeal to people of all ages, races, occupations or whatever,” He wrote. “So don’t limit the game by excluding aliens or any other type of character or monster. If they don’t fit what you feel is what the game is all about, don’t just say ‘NO!,’ whittle on them a bit until they do fit.” (Vol. II, p.99)

He tore up the D&D rules and offered wild changes. His specific rules hardly mattered. The message mattered: Hargrave encouraged me to own the rules and my games and to create a game that suited me and my players.

For more, see “Once subversive, the Arduin Grimoire’s influence reaches today’s games.”

Melee (1977) and Wizard (1978)

Over my first years years of playing D&D, the fun of the game’s battles waned. My games drifted away from the fights, and toward exploration and problem solving.

Game designer Steve Jackson understood the trouble. In Space Gamer issue 29, he wrote, “The D&D combat rules were confusing and unsatisfying. No tactics, no real movement—you just rolled dice and died.” Steve turned his desire for better battles into elegant rules.

Game designer Steve Jackson understood the trouble. In Space Gamer issue 29, he wrote, “The D&D combat rules were confusing and unsatisfying. No tactics, no real movement—you just rolled dice and died.” Steve turned his desire for better battles into elegant rules.

In the late 70s, ads in Dragon magazine convinced me to spend $2.95 on Jackson’s combat game Melee and $3.95 on the magic addition Wizard. I half expected to be disappointed. Role playing games required hefty books, and Melee and Wizard were not even full role playing games, just tiny pamphlets with paper maps and cardboard counters.

I loved playing the games so much that they changed the way I played D&D.

The revelation came from the map and counters. You see, despite D&D’s billing as “Rules for Fantastic Miniature Wargames,” I had never seen miniatures used for more than establishing a marching order. From local game groups to the D&D Open tournaments at Gen Con, no combats used battle maps, miniatures, counters, or anything other than the theater of the mind. Miniatures struck me as a superfluous prop, hardly needed by sophisticated players. The idea of bringing a tape measure to the table to measure out ranges and inches of movement seemed ridiculous.

I failed to realize how limited we were by theater of the mind. Without a map, nobody can really follow the action unless things stay very simple. In practice, you could be in front, swinging a weapon, or behind the fighters, making ranged attacks. Two options. If you were a thief, you could also try and circle around to backstab. As Steve Jackson wrote, “You just rolled dice and died.”

Melee and Wizard included hex maps and counters and simple rules for facing, movement, and engagement. After just one game, I felt excited by all the tactical richness that I had formerly snubbed.

For more, see “Melee, Wizard, and learning to love the battle map.”

Runequest (1978)

With Dungeons & Dragons, Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax invented the role-playing game. With Runequest, Steve Perrin and Ray Turney showed how to design a role-playing game.

Steve Perrin first entered the hobby when he distributed his D&D house rules, “The Perrin Conventions,” at DunDraCon in 1976. This led to Runequest, a game that replaced every aspect of D&D with more flexible, realistic, and simpler alternative: Skills replaced the confining class system. Experience came from experience, not from taking treasure. Armor absorbed damage from blows that landed. Combat simulated an exchange of blows, dodges and parrys. Damage represented actual injuries. Rather than a hodge-podge of mechanics, Runequest introduced the idea of a core mechanic that provided a way to resolve every task. Rather than the game setting implied by all of Gary’s favorite fantasy tropes, Runequest supported Glorantha, a unique world built as a consistent, logical setting.

Suddenly, D&D’s rules seemed as dated as gas lights and buggy whips. I enjoyed an occasional D&D game, but I switched to electric lighting until D&D adopted much of the same technology for third edition.

Today, simulation seems less important than in 1978. I now see that rules that made D&D unrealistic also added fun by enabling the game’s combat-intensive dungeon raids. For more, see “The brilliance of unrealistic combat” and “The fun and realism of unrealistically awarding experience points for gold.”

However, elegance remains as important as ever. Aside from earlier editions, D&D’s current design owes more to Runequest than any other game. Third-edition D&D’s lead designer Jonathan Tweet called Runequest the role-playing game that taught how to design RPGs. Actually, Runequest taught everyone how.

Jonathan Tweet credits Runequest with a long list of innovations that reached D&D.

- prestige classes (rune lords, rune priests, and initiates)

- unified skill-combat-saving-throw system

- ability scores for monsters

- 1 in 20 hits are crits

- ability scores that scaled up linearly without artificial caps

- a skill system that let anyone try just about anything

- armor penalties for skill checks and spellcasting

- creature templates

- faction affiliations

- hardness for objects

- chance to be hit modified by Dexterity and size

- iconic characters used in examples throughout the rule book

- rules for PCs making magic items.

Next: 1978-2000

I started with OD&D, but Holmes is the first FRPG I owned and it is still my first crush. I had CSotIO and spent endless hours pouring over it. I’m sad that I don’t know what ever happened to them. The Arduin books always fascinated me. I got to glance through a friend’s copies, but never had a set of my own. I think an original set is probably at the top of my gaming wish list. I’ve never looked at RQ though. Somehow it never spoke to me, but I probably should take a look. Melee was fantasic! I played with it briefly and never had Wizard, but I remember loving the game. Good memories.

One game I would add to your list is Dragon Quest. I only got to play it a couple of times, but I really enjoyed reading the books. It had some interesting ideas.

Hi Old Guy,

I played DragonQuest at a con once and feel an affection for the game. Coming from SPI, DragonQuest seemed to boast a wargame’s rigor without getting mired in detail. Jennell Jaquays considers her DragonQuest adventure The Enchanted Wood (written using the name Paul) her finest adventure.

–

Dave

A lot of us have come around to the idea that D&D’s odd mechanics actually were what allowed it to be so much fun. I spend most of the 80s and 90s using RuneQuest and HarnMaster, and what we created with those was as fun as anything we ever did, they didn’t allow for the same things that D&D did — they were too finely detailed for big battles and extended, unrealistic forays into the unknown.

And PS: the classic RQ2 is being republished via KickStarter.

Andrew,

I suspect you arrived at this conclusion sooner than I did, but my outlook transformed when I finally realized that some of the things that made D&D unrealistic also made it fun.

–

Dave

Agreed!

You nailed it, “some of the things that made D&D unrealistic also made it fun.”

Thanks for the great blog as usual!

s release, new role-playing game writers and publishers began releasing their own role-playing games, with most of these being in the fantasy genre. Some of the earliest other role-playing games inspired by

Thank you! You brought me back to some things I had long forgotten.

Tegel Manor and City State plus the surrounding Wilderlands of High Fantasy shifted things radically for us.

I didn’t get to Runequest although Pendragon based on that occupied us a great deal in the later 80s.

Melee I was introduced to during a period of months in Tokyo. It had a similar effect on me and when I got back to the states my notions inspired by that game merged with another friend’s and sheets of acetate, china markers, and miniatures (you mean you can use them individually instead of mounted in units???!!!) *expanded* theater of the mind in wonderful ways.

The other game that I don’t blame you for including was Traveller. While it was Science Fiction it too espoused streamlined, unified mechanics and systems and inspired us with the possibilities of a wide ranging but cohesive milieu in which to play.

Again, thank you, both for the memories and for your insight as to how these things influenced the development of the game.