As introduced in the original Dungeons & Dragons supplements, the astral and the ethereal planes seemed like two names for the same place. D&D characters visited both planes for the same reason: to snoop undetected. Either way, travelers pass through walls. On both planes, travelers braved the psychic wind. Monsters with attacks extending to one dimension invariably touched the other as well. The two planes shared the same encounter tables.

Today, thanks to decades of new planar lore, the astral and ethereal now differ. Instead of psychic winds, ethereal travelers face ether cyclones. On both planes, travelers fly around at will, but on the ethereal, creatures have a sense of gravity. Planar diagrams show the astral plane touching outer planes like the Hells and Limbo, while the ethereal touches the elemental planes. (Nonetheless, characters will still use plane shift and portals to travel the planes.)

Today, thanks to decades of new planar lore, the astral and ethereal now differ. Instead of psychic winds, ethereal travelers face ether cyclones. On both planes, travelers fly around at will, but on the ethereal, creatures have a sense of gravity. Planar diagrams show the astral plane touching outer planes like the Hells and Limbo, while the ethereal touches the elemental planes. (Nonetheless, characters will still use plane shift and portals to travel the planes.)

Despite these differences, when the fourth-edition designers simplified the lore in their Manual of the Planes (2008), they dropped the ethereal plane. No wonder fans felt incensed!

How did D&D wind up with the Coke and Pepsi of planes? Do their redundancies just add useless complication to the game’s cosmology as the fourth edition designers seemed to conclude?

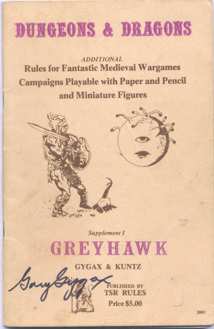

Two magic items that appeared in Greyhawk (1975) introduced the ethereal to D&D. Both oil of etherealness and armor of etherealness put characters “out of phase,” letting them through solid objects and making them immune to attack except by other creatures that can also become out of phase. Only a mention of creatures that can see ethereal things reveals that ethereal travelers are invisible rather than merely intangible.

Two magic items that appeared in Greyhawk (1975) introduced the ethereal to D&D. Both oil of etherealness and armor of etherealness put characters “out of phase,” letting them through solid objects and making them immune to attack except by other creatures that can also become out of phase. Only a mention of creatures that can see ethereal things reveals that ethereal travelers are invisible rather than merely intangible.

One spell that debuted in Greyhawk introduced the astral to D&D. The astral spell let casters send their astral form out of their body. The form can fly at the speed of 100 miles per hour or more “and nothing but other astral creatures could detect it.” so the spell offered a superb way to find the best treasures and the worst traps in the dungeon.

The astral spell offers no more detail about astral travel, but fantasy gamers in the early 70s likely understood the concept. In Doctor Strange’s comic book appearances of the time, the Sorcerer Supreme frequently traveled in ethereal, astral, or ectoplasmic form; the superhero’s writers used the terms interchangeably. Gary Gygax included every idea he found in fantasy and folklore in his game, and gamers in his circle knew Doctor Strange. Brian Blume, the co-owner of D&D publisher TSR, was a fan. The teenage artist Gary recruited to draw the original D&D cover patterned the image after a panel in a Doctor Strange comic. Gamers could also consult books like the Art and Practice of Astral Projection (1975). Back then, astral projection attracted popular attention and even the U.S. Army took the paranormal seriously enough to launch a research effort that included astral projection.

The Eldritch Wizardry supplement (1976) frequently mentions ethereal and astral travel together, making the two dimensions interchangeable except for the magic item or spell required to reach them. The distinction between oil of etherealness and astral spell created one big difference in play. The oil made the body ethereal, so when the effect wore off, the user gained substance wherever they had traveled. With the astral spell, the caster’s astral form left their body behind and then returned to their body when the spell wore off or when something destroyed their astral form. This let someone scout while nearly immune to harm, but they could not physically travel to another place.

Until the plane shift spell debuted in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Player’s Handbook (1978), characters could not bring their bodies to the astral plane. Plane shift enabled travel to and from the astral and ethereal, making visiting either plane equally simple.

In the AD&D Player’s Handbook, Gary’s urge to gather ideas from other sources led him to complicate the astral spell with more lore from astral projection. Some real-world investigators into astral projection claimed that during their out-of-body experiences, they saw an elastic, silver cord that linked their astral form to their physical body. Based on this, the astral spell added cords that tether astral travelers to their flesh and blood. Breaking the cord kills the traveler, so the cords potentially add some risk and tension to astral projection, even though “only a few rare effects can break the cord.” When Charles Stross created the astral-dwelling githyanki for the “Fiend Factory” column in White Dwarf issue 12 (1979), he wisely gave them swords capable of cutting the silver cords, adding some real peril to astral travel.

In the July 1977 issue of Dragon magazine, Gary Gygax printed a diagram that showed a difference between the astral and ethereal planes. The astral stretched to the outer planes like Olympus and the Hells, while the ethereal reached the inner, elemental planes. This proximity hardly made a difference in gameplay, since Gary never explains how astral travelers can navigate to Olympus, or why someone might care in a game with plane shift on page 50 of the Player’s Handbook. Besides, with Queen of the Demonweb Pits still years away, a DM who allowed players to travel the planes lacked any example to follow.

In the July 1977 issue of Dragon magazine, Gary Gygax printed a diagram that showed a difference between the astral and ethereal planes. The astral stretched to the outer planes like Olympus and the Hells, while the ethereal reached the inner, elemental planes. This proximity hardly made a difference in gameplay, since Gary never explains how astral travelers can navigate to Olympus, or why someone might care in a game with plane shift on page 50 of the Player’s Handbook. Besides, with Queen of the Demonweb Pits still years away, a DM who allowed players to travel the planes lacked any example to follow.

As far as players cared, the astral and ethereal just offered ways to snoop while undetectable and unblocked by walls. The choice of plane depended on the available magic. In 1977, D&D co-creator Gary Gygax would write about how astral and ethereal travel “posed a headache for DM’s.” In Tomb of Horrors (1978), he writes “Characters who become astral or ethereal in the Tomb will attract a type I-IV demon 1 in 6, with a check made each round.”

As far as players cared, the astral and ethereal just offered ways to snoop while undetectable and unblocked by walls. The choice of plane depended on the available magic. In 1977, D&D co-creator Gary Gygax would write about how astral and ethereal travel “posed a headache for DM’s.” In Tomb of Horrors (1978), he writes “Characters who become astral or ethereal in the Tomb will attract a type I-IV demon 1 in 6, with a check made each round.”

The Manual of Planes (1987) finally created differences between the astral and ethereal that factored into game play.

The astral no longer overlapped the material plane, so astral travelers lost the power to scout and spy. At best, astral travelers could find a portal called a color pool leading to the material plane and use it as a window to scry. Instead, the astral became a crossroad of connections to other planes. The astral gained those color pools and also conduits that work like portals but looked different. Years later, the fourth-edition designers fully realized this idea of the astral connecting to the outer planes when it made the Heavens, Hells, and other outer planes domains floating in the astral sea.

The ethereal still allowed invisible, intangible scouting, but it now extended into the deep ethereal, a place that connected to the elemental planes and various demi planes. The deep ethereal seems like a useless complication that stems from a diagram Gary printed in that 1977 issue of Dragon, because it resembles the astral plane, and besides players travel by plane shift and portal.

The ethereal still allowed invisible, intangible scouting, but it now extended into the deep ethereal, a place that connected to the elemental planes and various demi planes. The deep ethereal seems like a useless complication that stems from a diagram Gary printed in that 1977 issue of Dragon, because it resembles the astral plane, and besides players travel by plane shift and portal.

By the 90s, as D&D settings started proliferating, D&D designers started looking for ways to connect them. The Spelljammer setting gave characters a way to pilot their fantasy spaceships between Faerûn, Krynn, Oerth, and so on. The Planescape setting uses the deep ethereal to create similar connections between D&D worlds.

The astral and deep ethereal are different thanks to Coke versus Pepsi nuances of flavor and because each plane led to different places. (Does that feel like too much complexity for few gameplay rewards?) In practice, plane shift and portals mean that few visit the astral except to fight githyanki and no one visits the deep ethereal ever. In today’s game, the new Spelljammer setting uses the astral sea to connect D&D worlds, leaving the deep ethereal with no reason to exist. (Update: The Radiant Citadel of Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel exists in the deep ethereal, which provides the feel of a magical place disconnected from the ordinary, but without the problems created by locating a city in the astral where nothing ages.)

If I were king of D&D, I would adjust the astral and ethereal with some changes:

- Drop the deep ethereal, keeping the ethereal as the sole, overlapping plane of creatures out of phase. The deep ethereal rates a description in the 2014 Dungeon Master’s Guide, but I suspect no fifth-edition character has ever visited it.

- Drop the astral projection spell and the silver cords. The ability to spy from the astral plane disappeared in 1987, so the astral spell just rates as a pointless nod to a passing interest in the paranormal.

- Make the astral sea the plane of portals and conduits that serves as the crossroads of worlds and planes.

Related: Queen of the Demonweb Pits Opened Dungeons & Dragons to the Planes