The media keeps telling us how we, the geeks, have won popular culture. Golfers chat about Game of Thrones at the country club. A minister I know boasted that she was a member of her high school Dungeons & Dragons club. The Return of the King won best picture. Fan culture is everywhere. So we forget that in the early days, when D&D burgeoned by word-of-mouth, no one had seen anything like it.

Of course, little in D&D stands as completely new. The book Playing at the World devotes hundreds pages exploring threads of influence. But in the 70s, unless you joined a tiny cult of miniature gamers interested in fantasy, you would have never seen the game coming. Unless you followed a few, obscure genre authors, you would never have seen anything like it. You shared popular assumptions that D&D would explode.

1. Fantasy is for children and a few oddballs.

Forget the The Lord of the Rings, and then name a work of fantasy that was widely known before D&D. Anything you name is a fairytale or fable—something for children. Conan? He’s a comic book character. Every grown up knows comics are for children. Now consider The Lord of the Rings. It enjoyed enough popularity to get cited by Led Zeppelin and some other long hairs, but when Hollywood tried to trade on its popularity, they added musical numbers. Hollywood did not think they could reach a big enough audience of oddballs, so they adapted for children.

As a kid in the 70s, All the fantasy I knew came from picture books. Stories where trolls lived under bridges and bugbears under beds. Nothing prepared me for a game inspired by Appendix N. A game where trolls lived in dungeons and refused to die. The original Monster Manual revealed beholders, mind flayers, chromatic dragons and countless other dreadful wonders that filled me with excitement.

The public’s unfamiliarity with fantasy contributed to the panic that surrounded D&D in the 80s. God fearing adults saw their teenagers obsessed with spells and children’s fairy tale nonsense, but darker and more violent. They settled on the only logical explanation, demon worship, because the culprit could not possibly be a really fun game.

Meanwhile, I worked to find the books named in The Dragon’s Giants in the Earth column and later in Appendix N. I found none. Admittedly, I suffered the disadvantage of shopping from a mall bookstore. I knew nothing of used book stores or inter-library loan. Nonetheless, few of Gary’s inspirations remained in print. Today, fantasy books of all stripes crowd the shelves. Then, I took years to collect the books that inspired the game.

2. Games are terrible.

In the 70s, games sold as toys and they were all terrible. They suffered from stupid, and random mechanics: Roll a die and move that many spaces. The winner becomes obvious long before the end, yet they took forever to finish. Games covered prosaic subjects like Life and Payday, or financial wish-fulfillment like Monopoly or, well, Payday. Still, I liked games enough that I even played terrible ones endlessly. (Except, of course, for Monopoly, which I suspect Hasbro makes to convince millions that games are tedious. I cannot fathom their plot’s endgame.) My standards were so low that I liked the 1974 game Prize Property where you launched legal actions against your opponents to stall their building developments. Legal actions. The box claimed fun for ages 9 and up.

People suffered from narrow ideas about what a game could be. Someone wins, someone loses, the game never extends past the board and never continues after you close the box.

Before I saw D&D, I sat with a sheet of graph paper and tried to imagine how the game would play. Working from a 12-year-old’s lunch-room pitch, I got nowhere. From my experience rolling a die and moving that many squares, I had no clue how a game could allow the things the kids claimed.

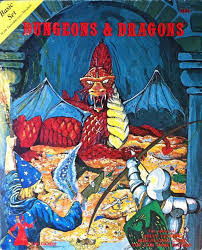

So in a mere 48 pages, the Holmes Basic D&D rule book shattered my notion of what a game could be.

So in a mere 48 pages, the Holmes Basic D&D rule book shattered my notion of what a game could be.

Later, when I described the new game, everyone asked the same questions: “How do you win?” and then, “if you can’t win, what’s the point?” Everyone struggled to grasp the notion that you played to have fun without any chance of winning. For more, see “But how do you win?”

3. Adults cannot play act a role.

People sometimes say that D&D did not invent the role-playing game. Kids have always role played; we just called it make believe. Saying that D&D just brought make believe to adults misses the true innovations. The revolution came from playing a character with stats that carried to the next session, and from the idea that characters gained experience and improved. In Playing at the World, while describing D&D’s reception, Jon Peterson shows new players and reviewers always touting the experience system. The steady reward of experience and levels forged an obsession for many players. The combination proved so compelling that just about every computer role-playing game borrows it.

For more, see “The fun and realism of unrealistically awarding experience points for gold.”

Meanwhile, parents feared that playing a role in D&D would lead their children to confuse fantasy with reality. After all, wasn’t anyone old enough for such a complicated game too old for make believe? Kids talked about being a wizard or a thief and responsible citizens worried that kids believed it. The D&D panic stemmed as much from this unfamiliar blurring of reality as from spells and demons.

4. Dungeons are just medieval jails.

Zombies and vampires appear everywhere in popular culture. Both archetypes seem medieval, but the popular conception of zombies only dates back to George Romero’s 1968 movie Night of the Living Dead.

The concept of a dungeon as an underground sprawl with monsters and treasures, is even newer.

In the fantasies that inspired the game, no character explores a dungeon. At best, you can find elements of the dungeon crawl, such as treasure in the mummy’s tomb, orcs in Moria, traps in a Conan yarn, and so on.

Now, the dungeon adventure qualifies as a trope that appears in virtually every computer fantasy game.

In my world before D&D, games gave the fun of launching legal action against fellow real estate developers. When I opened the basic rules, I could brave the peril and mystery of the dungeon shown in the Stone Mountain cross section. Still today, no image inspires my enthusiasm to play as much. I jumped from property law to Greyhawk.

For more, see “From Blackmoor to Dungeons & Dragons: The invention of the dungeon crawl.”

By the end of the 70s, fandom had yet to dominate popular culture, but Star Wars and Superman and Dungeons & Dragons had established a beachhead. The gains would only continue.

For me, the 48 pages of the 1977 Basic Set did more than introduce the best game in the world, those pages turned some of what I understood upside down.