(Part 4 of a series, which begins with Evolution of the skill challenge.)

Just a year after fourth edition’s debut, the Dungeon Master’s Guide 2 upended the original skill challenge. The new material makes just one specific revision to the original rules: It provides new numbers for challenge complexity and difficulty class to address serious problems with skill challenge math.

Beyond the numbers, I suspect the designers sought to remake the skill challenge as much as possible without scrapping the existing rules. The big changes come from original rules that are now ignored, and from advice and examples that completely remake how challenges run at the table.

The Dungeon Master’s Guide 2 strips away the formal game-within-a-game implied by the original skill challenge: The structure of rolling for initiative and taking turns is gone; the new summary contains no mention of it. In the example skill challenge, the players jump in to act as they wish.

I disliked the original, story-game style implied by the original skill challenge rules, and welcomed the new advice. But the core of the original skill challenge rules remained, and some friction existed between those original rules and the recast skill challenge. In this post, I will explore some points of friction, and discuss some ways to overcome them.

Scoring with failed checks discourages broad participation

The 4E designers tried the match the formulas for constructing a combat encounter with similar formulas for a skill challenge. So a skill challenge’s complexity stems from the number and difficulty of successes required─an odd choice in a way. You don’t grant experience in a combat encounter by counting how many attacks score hits.

This scorekeeping works fine when you run a skill challenge as a collaborative storytelling game within a game

In the original skill challenge, every character had a turn, and no one could pass. This forced every player to participate. The new challenge drops the formal structure, leaving the DM with the job of getting everyone involved. The DMG2 helps with advice for involving every character. However, the players know three failed skill checks add up to a failed challenge, so now some players will fight against making any checks for fear of adding to an arbitrary count of failures and contributing to a failed challenge. This stands in total opposition to the original ideal where everyone contributes.

Obviously, some failed skill checks will bring the players closer to a disaster, by alerting the guards, collapsing the tunnel, or whatever. On the other hand, the foreseeable, game-world consequences of some failures do not lead to disaster, yet players worry about attempting, say, an innocuous knowledge check because they metagame the skill challenge.

Hint: You can encourage more players to participate in a skill challenge by forcing the characters to tackle separate tasks simultaneously. For instance, if the characters only need to gain the support of the head of the merchant council, then typically one player makes all the diplomacy rolls. If the characters must split up to convince every member of the merchant council before their vote, then every player must contribute. Just give the players enough information to know which methods of persuasion will work best on which members of the council.

Scorekeeping may not match game world

In the story-game style of the original skill challenge, the players’ score can exist as a naked artifice of the game, just like the turns the rules forced them to take. I suspect that the original vision of the skill challenge assumed the DM would tell players their score of successes and failures. After all, the players could even keep accurate score themselves. This avoided the need to provide game-world signs of success or failure as the players advanced through the challenge. After the skill challenge finished, you could always concoct a game-world explanation for the challenge’s outcome.

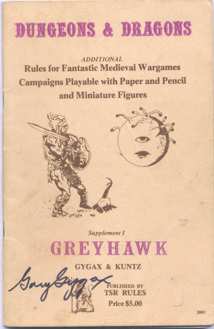

Now on page 83, the DMG2 tells you to “grant the players a tangible congruence for the check’s success or failure (as appropriate), one that influences their subsequent decisions.” (In word choices like “tangible congruence,” Gary’s spirit lives!)

This works best if the challenge’s cause of failure is different from the players’ success. For example, if the players must infiltrate the center of the enemy camp without raising an alarm, then their successes can bring them closer to their goal even as their failures raise suspicion and take them closer to failure. These sorts of challenges create a nice tension as the players draw closer to both victory and defeat.

If moving toward success necessarily moves the players away from failure, then running the challenge poses a problem.

The first Dungeon Masters Guide introduced the skill challenge mechanic with an example where the players attempt to persuade the duke before the duke grows too annoyed to listen. Good luck role playing the duke’s demeanor as he is poised one success away from helping while also one failure away from banishing the players.

The first Dungeon Masters Guide introduced the skill challenge mechanic with an example where the players attempt to persuade the duke before the duke grows too annoyed to listen. Good luck role playing the duke’s demeanor as he is poised one success away from helping while also one failure away from banishing the players.

Even worse, if a skill challenge lacks any clear marker of failure, running the challenge presents a problem. The first D&D Encounters season, Halaster’s Last Apprentice, included a challenge where the players seek to find hidden chambers in the Undermountain before they amass the three failures allowed by the rules. Why do three failures end this challenge? Is it because the players grow restless and are now all on their smart phones? The adventure suggests that rival groups might be seeking the lost chambers, but it fails to capitalize on this. The adventure follows the conventional advice by taxing each player a healing surge, and then saying that they found the crypt anyway.

“Why do we lose a healing surge?”

“Well, you know, dungeon stuff.”

Why is the game turning the dungeon stuff into a die-rolling abstraction? I thought some of us liked dungeon stuff.

Hint: You can fix a lot of bad skill challenges by adding time pressure. Every failed attempt wastes time. Too many failures and time runs out. Convince the duke before he is called to the wedding that will cement his alliance with the enemy. Find the hidden crypt before the sun sets and the dead rise.

Next: Spinning a narrative around a skill challenge

In 4E, as much as possible, players save an action point and their big daily powers for an expected climactic encounter. When that showdown with the boss comes, the characters unleash everything they have. Every pre-Essentials character can horde daily powers for the showdown, making the first round of attacks devastating. Action points allow characters to double the barrage of daily and encounter powers, making the onslaught twice as potent. By the time a guy like Juiblex, demon lord of slimes and oozes, gets a chance to act, he’s prone, immobilized, dazed, suffering -4 to all attacks, and has his pants around his ankles. (In fourth edition, even oozes are subject to the pants-round-ankles condition.)

In 4E, as much as possible, players save an action point and their big daily powers for an expected climactic encounter. When that showdown with the boss comes, the characters unleash everything they have. Every pre-Essentials character can horde daily powers for the showdown, making the first round of attacks devastating. Action points allow characters to double the barrage of daily and encounter powers, making the onslaught twice as potent. By the time a guy like Juiblex, demon lord of slimes and oozes, gets a chance to act, he’s prone, immobilized, dazed, suffering -4 to all attacks, and has his pants around his ankles. (In fourth edition, even oozes are subject to the pants-round-ankles condition.)