If you play Dungeons & Dragons in game stores, you will meet an unfrozen dungeon master. Fifteen years ago, I was one.

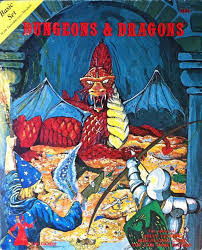

The first surge in the popularity of D&D started in 1977, when I found the first Basic Set, and continued in the 80s. Nerdy kids everywhere found the game, played obsessively, and then mostly moved on. Eventually groups separated for college and jobs. Players abandoned their books in their parents’ attics or sold them for gas money.

The first surge in the popularity of D&D started in 1977, when I found the first Basic Set, and continued in the 80s. Nerdy kids everywhere found the game, played obsessively, and then mostly moved on. Eventually groups separated for college and jobs. Players abandoned their books in their parents’ attics or sold them for gas money.

But we missed the game, and 10, 20, or 30 years later, those of us who loved D&D come back. We are the unfrozen dungeon masters.

Over the years, D&D has changed. Not just the rules, but also play style and player expectations have changed. When unfrozen DMs play, we can either adapt to the new style—shaped by 45 years of innovation. Or we can find like-minded players in the old school—still as fun as ever.

An unfrozen DM came to my local store during the fourth-edition era. He played enough to learn the new edition and then served as a DM on a Lair Assault. After the game, he told me about the rules he fixed on the fly because they didn’t suit him or his style of game. Such changes defied the spirit of fourth edition, which aimed to limit DM meddling in favor of giving players a clear understanding of how their actions will play in the game world. Such DM fiat especially defied the spirit of a competitive challenge like Lair Assault.

Since then, I haven’t seen a DM so clearly unfrozen, but DMs still stagger from caves and icebergs into game stores. When they run a game, newer players probably see too much focus on pitting an unyielding game world against the party, and too little on shaping the game to suit the players and their characters.

This topic inspired a question that I asked on Twitter. The answers showed the gulf between the game when I started playing and the current style of play. I felt a little like a DM staggering from melting ice to see a new world of wonders. Will I ever learn enough of the new ways to fit in?

When D&D started, DMs were called referees and they played the part of a dispassionate judge of the game. As a referee, you used die rolls to place most of the monsters and treasure in your dungeon. When the players explored, you let die rolls and the players’ choices determine the outcome. A referee ran home adventures the same they ran a tournament where competing teams might compare notes and expect impartial treatment.

D&D’s roots in wargaming set this pattern. Referees devised a scenario in advance. Players chose sides and played. In the spirit of fairness, referees didn’t change the scenario on the fly.

Chivalry & Sorcery (1978), one of D&D’s early imitators, spells out this ideal. The rules advised the GM to set out a dungeon’s details in advance so he could “prove them on paper should an incredulous group of players challenge his honesty or fairness.”

That style didn’t last. In most D&D games, no competing team watches for favoritism, so if the DM changes unseen parts of the dungeon, the players never know.

Dungeon masters differ from referees in other ways.

Unlike wargames with multiple sides, dungeon masters control the foes who battle the players. Now, DMs sometimes struggle to suppress a will to beat the players. In the 1980s, when people still struggled to understand a game that never declared a winner, competitive urges more often proved irresistible.

“RULE NUMBER ONE in Chivalry & Sorcery is that it is a game, not an arena for ‘ego-trippers’ to commit mayhem with impunity on the defenseless or near defenseless characters of others. Games have to be FUN, with just enough risk to get the adrenalin pumping. The moment that an adventure degenerates into a butchering session is the time to call a halt and ask the would-be ‘god’ running the show just what he thinks he is doing, anyway.”

All of the early fantasy RPGs came as reactions to D&D. For example, Tunnels and Trolls (1975) aimed to make D&D accessible to non-grognards—to players who didn’t know a combat results table from a cathode ray tube. C&S follows the pattern. It reads as a response the shortcomings of D&D and the play style it tended to encourage.

C&S reveals much about how folks played D&D in the early years.

Before I entered the DM deep freeze, my players would sometimes discuss their plans of action out of my earshot. In their talks, as they speculated on the potential threats ahead, they imagined worst-case scenarios. To avoid giving me ideas, they kept me from overhearing. After all, their worst-case scenario might be harsher than anything I planned. (Obviously, I never borrowed the players ideas. My worst cases were always worse.)

D&D has changed since then, so I asked current players on Twitter for their feelings:

How do you feel about GMs who eavesdrop on your conversations, and then incorporate your speculations in the game?

- Love it. Let’s tell stories together.

- Hate it. The DM shouldn’t steal my ideas to complicate my character’s life.

In the responses, the lovers overwhelmed the haters to a degree that surprised me.

Players see RPGs are structured, collaborative storytelling and they enjoy seeing their ideas shape the tale. “D&D is a collaborative storytelling activity,” @TraylorAlan explains. “I imagine it as a writer’s room for a TV show, with a head writer who has a plan that is modified by the other writers. A good DM riffs off what players do, uses that to build. Players then feel invested because their choices matter.”

I agree, but my sense of the answers is that folks don’t often imagine their DM overhearing a worst-case scenario, and then wielding it against characters. If players only wanted compelling stories, DMs should sometimes adopt players’ cruelest ideas and use them. Stories feature characters facing obstacles. Countless sources of writing advice tell writers to torture their beloved characters. But how many players want to participate in the torture of their alter egos?

For my money, the answer to my question depends on the part a DM plays in the game, moment by moment.

Are you the adversary, with a Team Evil button?

Better to keep your eyes on your own paper, even if the players’ worst-case scenario fills you with glee. Never adopt killer strategies or dream up countermeasures for tactics you overhear.

Are you the collaborative story-teller, looking to help the players reveal their characters?

When players speculate at the table, they’re making connections based on what they know about the game world—connections that the DM may not see. Adopt the speculations that link the characters to the game world in unexpected ways. They reveal they characters and tie them to the shared fantasy. Making connections real makes the D&D world seem deeper and more meaningful. It adds a sense of order that we humans enjoy in the game world, especially at times when the real world shows too little order and too little sense.

The twenty-sided die may not have reached Dave’s corner of gaming yet, but Gary had funny dice and they enchanted him. At first, polyhedral dice only came from vendors in Japan and the United Kingdom, so getting a set required significant time and money. But by 1972, polyhedral dice started arriving from domestic sources. Gary recalled buying his first set from a teacher-supply catalog. In 1972, Creative Publications of California started selling 20-sided dice in a set of polyhedrals, and word spread among gamers. By 1973, Gary

The twenty-sided die may not have reached Dave’s corner of gaming yet, but Gary had funny dice and they enchanted him. At first, polyhedral dice only came from vendors in Japan and the United Kingdom, so getting a set required significant time and money. But by 1972, polyhedral dice started arriving from domestic sources. Gary recalled buying his first set from a teacher-supply catalog. In 1972, Creative Publications of California started selling 20-sided dice in a set of polyhedrals, and word spread among gamers. By 1973, Gary  D&D’s designers seemed to think rising armor classes made more sense. The game rules stemmed from co-creator Gary Gygax’s

D&D’s designers seemed to think rising armor classes made more sense. The game rules stemmed from co-creator Gary Gygax’s