An elegant role-playing game gains maximum play value out of a concise set of simple rules.

Elegant rules…

- apply broadly so fewer rules can cover whatever happens in the game.

- play quickly with minimal math and little need to reference or memorize.

- can be easily explained and understood.

- produce outcomes that match what players expect in the game world.

- enable players to anticipate how their characters’ actions will be resolved and the likely outcomes, something I call resolution transparency.

Rules-light role-playing games maximize economy by applying just a few rules across the entire game, but they sacrifice resolution transparency.

Dungeons & Dragons has never qualified as a rules-light system, but the game has grown more elegant by eliminating rules and applying the rules that remain more broadly. In “Design Finesse,” D&D patriarch Mike Mearls writes, “You’re more likely to introduce elegance to a game by removing something than by adding it.”

Elegant role-playing games start with economical rules, yet they still invite players into their characters, give them plenty of freedom to make interesting choices, and provide easy ways to resolve the actions so the outcomes make sense in the game world.

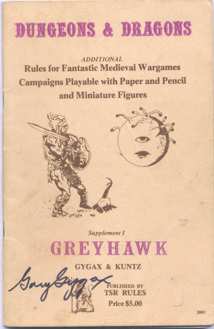

D&D started as an inelegant game: a bunch of mechanics that Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax dreamed up as they refereed, which Gary then wrote in his stream-of-consciousness style. In “A Brief History of Roleplaying,” Shannon Appelcline writes, “In various early versions of D&D and AD&D, you had one system to model Strength (a range of 3-17, then 18/01 to 18/00), one to model all the other characteristics (3-18), one to model armor class (10 to -10), one to model thief ability (0-100%), one to model skill in combat (a to-hit number from 20 to 1), one to model clerical spells (7 levels of magic), one to model magic-user spells (9 levels of magic), etc.”

Why so many systems? No one knew anything about RPG design, because none existed. Also, during D&D’s formative years, Gary was an incorrigible collaborator, always willing to add a friend’s new rule to the mix. Each of Gary’s brown-book D&D releases features the work of a different collaborator. Even in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Gary couldn’t say no to additions like weapon speeds and psionics—additions he regretted.

In 1977 and 1978, role-playing game design took two huge steps: Traveller introduced a skill system. Runequest united all action resolution around a core mechanic. These two games charted a course for elegant RPG design, and virtually all games to follow built on their innovations.

Second edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons cut some rules that no one ever used, but the system’s core remained mired in the RPG stone age. In a D&D podcast episode examining the second edition, designer Steve Winter said, “There were all kinds of changes that we would have made if we had been given a free hand to make them—an awful lot of what ultimately happened in third edition. We heard so many times, ‘Why did you keep armor classes going down instead of going up?’ People somehow thought that that idea had never occurred to us. We had tons of ideas that we would have loved to do, but we still had a fairly narrow mandate that whatever was in print should still be largely compatible with second edition.”

When 2E appeared in 1989, game publishers still limited new editions to corrections and tweaks. If a publisher wanted to create an incompatible new version of a game, they coined a new name, such as Megatraveller and Runequest: Slayers. Of second edition AD&D, Steve Winter says, “The [TSR] executives where terrified of the idea of upsetting the whole customer base and driving away customers, coupled with the idea that if we put out a new book, what happens to all the old books? We have stores with all these books. we won’t sell any new players handbooks for a year while we’re making the new edition because people will know what’s coming.” How different from the modern market, where people accuse publishers of issuing new editions just to spur sales?

It took the sale of TSR, and a new edition from Wizards of the Coast, to give D&D twenty-year-old innovations such as skills and a core mechanic. Third edition simplified by consolidating a myriad of different rules into the d20 check that gave the core system its name. On the whole, 3E isn’t simpler than AD&D, but it took the complexity budget earned through simplification, and used it to add depth to tactical combat and to character options.

Emboldened by the acclaim for the big changes in 3E, the 4E designers felt willing to outdo the changes. The designers attacked some complexities that the third-edition designers had kept as sacred cows. For instance, fourth edition eliminated traditional saving throws by consolidating their function with attack rolls.

Fourth edition tried for a simpler game by focusing on exception-based design. This principle makes trading card games such as Magic: The Gathering playable despite the tens of thousands of cards in print. The 4E designers built a system on a concise set of core rules, and then added depth by adding abilities and powers that make exceptions to the rules.

Even with 4E’s concise core, the thousands of powers and thousands of exceptions produced more rules than any prior edition. Still, no RPG delivers more resolution transparency than 4E. In sacrifice, the edition often fails to model the game world, creating a world with square fireballs, where you can be on fire and freezing at the same time, where snakes get knocked prone, and where you can garrote an ooze.

Among all the simplifications in 4E, only the use of standard conditions appear to remain in D&D Next.

Both 3E and 4E used more elegant rules to produce simpler core systems, but both editions grew as complicated as ever. In “D&D Next Goals, Part One,” Mearls writes, “New editions have added more rules, more options, and more detail. Even if one area of the game became simpler, another area became far more difficult to grasp.” The D&D Next designers aim to deliver a simpler, more elegant core game, and then to add options that players can ignore if they wish. “We need to make a game that has a simple, robust core that is easy to expand in a variety of directions. The core must remain unchanged as you add more rules. If we achieve that, we can give new players a complete game and then add additional layers of options and complexity to cater to more experienced gamers.”