In 1977, when I found the Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, I noticed that the dwarf description included a lot of fluff: stocky bodies, long beards, and an ability to detect slanting passages, shifting walls and new construction. I figured the slanting-and-shifting thing would never affect the game unless some dwarf skipped adventuring for a safer job as a building inspector. “Your rolling-boulder ramp isn’t up to code. Someone might not trip.”

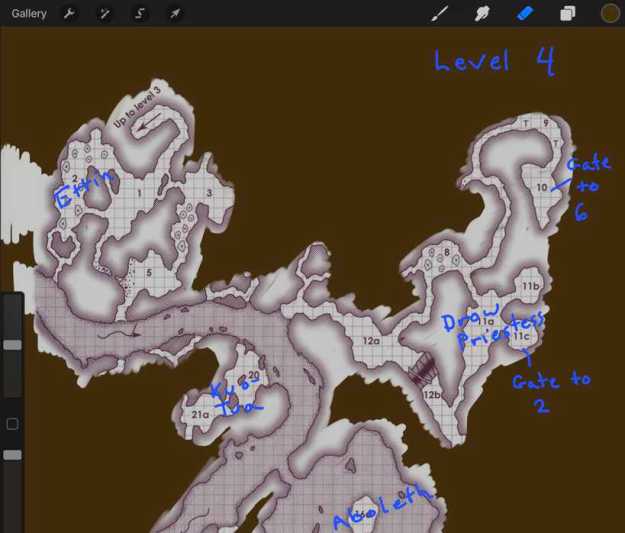

Years later, I realized the dwarven fluff actually helped players draw the accurate maps needed to keep characters alive. Sloping floors and shifting walls made more than a nuisance. In the mega-dungeons of the era, greater threats prowled on lower levels, so tricks that lured characters too deep threatened their lives. Lost explorers deep in a sprawling multi-level dungeon could run out of resources before they got out. Originally, the spell find the path found an escape path.

In early D&D, one player assumed the role of mapper and transcribed a description of walls and distances onto graph paper. The original rules present mapping as half of the game. In the example of play, the referee—the title of dungeon master had not been coined yet—spends half the dialog reciting dimensions. The rules’ example of “Tricks and Traps” only lists slanting passages, sinking rooms, and other ways to vex mappers. The text’s author, Gary Gygax, suggests freshening explored parts of the dungeon by adding monsters, but also through map “alterations with eraser and pencil, blocking passages, making new ones, dividing rooms, and filling in others.”

Despite the emphasis, many gamers found mapping less compelling. By 1976, the first D&D module Palace of the Vampire Queen included players’ maps to spare explorers the chore of transcribing dimensions. By fourth edition, labyrinths had changed from mapping challenges into skill challenges. Such mazes were no more fun, but they saved graph paper.

Today, only players who play D&D in an older style draw their own maps as they explore a dungeon.

Did anyone ever think translating distances to graph paper added fun? Or was mapping another way to thwart players who tried to steal the quasi-adversarial referee’s treasure. (In that original example of play, the Caller finds hidden loot, and the Referee responds by “cursing the thoroughness of the Caller.” Rules question: Must the Referee curse aloud or can he just twirl his mustache?

Blackmoor scholar Daniel H. Boggs describes mapping’s appeal. “If the DM is running the game with a proper amount of mystery, then mapping is one of the joys of dungeon exploring. In my experience, there is usually at least one person in the group who is good at it, and it is lots of fun to see your friends pouring over maps trying to figure out where to go or where some secret might be.”

In 1974, D&D seemed so fresh and intoxicating that even duties like mapping found love—just less love than the game’s best parts. Then, exploring a hidden version of the game board seemed revolutionary. Even the wargames that relied on umpires to hide enemies from opposing players let everyone see the terrain—and only a tiny community of enthusiasts played such games. In 1975, when Tunnels & Trolls creator Ken St. Andre attempted to explain dungeoneering to potential players, he could only reach for a slight match. “The game is played something like Battleship. The individual players cannot see the board. Only the DM knows what is in the dungeon. He tells the players what they see and observe around them.”

As fans of competitive games, D&D co-creators Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax relished tests of player skill more than many D&D players do now. To the explorers of the mega-dungeons under Blackmoor and Greyhawk, map making became proof of dungeoneering mastery. In the game’s infancy, different groups of players mounted expeditions as often as Dave and Gary could spare them time. Separate groups might compile maps and keep them from rivals.

While recommending slanting passages and sinking rooms, Gary seemed to relish any chance to frustrate mappers. Describing a one-way teleporter, he crows that “the poor dupes” will never notice the relocation. “This is sure-fire fits for map makers.”

Dave favored fewer tricks. Daniel Boggs writes, “Arneson would actually help map for the players by drawing sketches of what players could see in difficult to describe rooms.” In early 1973, Dave Megarry, a player in the Blackmoor campaign and designer of the Dungeon! board game, mapped much of Blackmoor dungeon during play. Megarry’s maps proved more accurate than the versions published in The First Fantasy Campaign (1980), a snapshot of Arneson’s Blackmoor game.

Still, Dave Arneson expected players to show mapping skill and deal with setbacks. In a 2009 post on the ODD74 forum, he wrote, “A referee ‘happy moment’ was when the mapper was killed and the map lost. ‘OK guys now where are you going?’ What followed was 15 minutes of hilarious, to me, fun. A non-player character gave them a general direction. Another was when the mapper died and the players couldn’t figure out how to read the map. Again an NPC saved them.”

“In terms of tricks, Arneson primarily relied on complexity,” Boggs writes. Despite ranking as the first dungeon ever, Blackmoor includes rare vertical twists. “The combination of connecting shafts, pits, elevators, and literally hundreds of stairs across levels is just astounding. There is also the fact that the dungeon is segmented, so portions of certain levels could only be accessed by stairs on other levels or via secret doors. Secret doors abound in Blackmoor dungeon and most of Arneson’s dungeons.”

Nowadays, the task of transcribing explored rooms and halls to graph paper lacks its original novelty, but turning unexplored space into a map brings as much satisfaction as ever. Sometimes as my players explore, I draw the map for them on a grid. For some sessions, I bring a dungeon map hidden by scraps of paper fastened with removable tape. Players can become so eager to reveal rooms that they vie for the privilege of peeling away the concealment. While running Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage, I loaded the maps on a tablet and concealed them under an erasable layer. All these techniques eliminated the chore of mapping for the pure fun of discovery.

If players’ enthusiasm reveals the fun in D&D, then not every part of the original game passes the test—at least for most players. Over five editions, the game has lost some things that few players enjoyed. Only players seeking a deliberately old school style embrace things like mapping, strict encumbrance, spell blowback, and damage to treasure.

If players’ enthusiasm reveals the fun in D&D, then not every part of the original game passes the test—at least for most players. Over five editions, the game has lost some things that few players enjoyed. Only players seeking a deliberately old school style embrace things like mapping, strict encumbrance, spell blowback, and damage to treasure.