In “Puzzle traps,” I explained how the most fun traps come with clues that alert players to the danger. I listed a few reasons why clues might accompany traps even though their builders want them to be unnoticed.

In addition to the accidental clues I suggested for puzzle traps, Dungeons & Dragons features a long tradition of tricks and puzzles constructed in a dungeon builder’s effort to test and confound intruders.

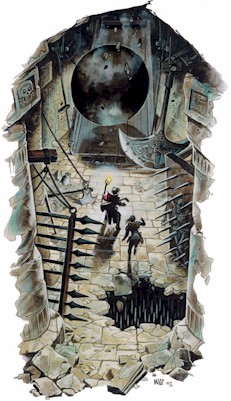

C2 The Ghost Tower of Inverness

Most players enjoy these sorts of conundrums. Funhouse dungeons filled with odd challenges such as White Plume Mountain and Ghost Tower of Inverness rate as some of the most beloved adventures of Dungeons & Dragons’s golden age.

But why would any dungeon builder construct a room that forced intruders to answer riddles or to move like chess pieces on a huge board? Traditionally, dungeon authors provided one of two answers:

-

“The builder was crazy.”

-

“Are you going to keep asking annoying questions or are you going to play the game?”

Unless your players signed up to play in a game set in 1978, dungeons built by insane, magical pranksters no longer seem fresh or plausible; the life-size chess boards and reverse-gravity rooms can feel tired and silly. Also, while the crazy-wizard premise offers dungeon authors complete freedom, it gives little backstory to serve as a source of inspiration.

Still, Keraptis, Galap-Dreidel, and I all share an affection for pitting adventures against a strange and confounding room, so I will list some other reasons why a dungeon’s architects might build in clues and tests for intruders.

Some of these reasons assume that a dungeon exists to help guard or defend something: treasure in tombs, powerful or dangerous items in vaults, creatures in lairs or prisons. These dungeons’ built-in challenges allow worthy intruders through, and tempt the unworthy to die trying.

A test of merit

From the sword in the stone to the quest for the princess’s hand, fantasy offers plenty of examples of tests to reveal the worthy. A dungeon’s challenges could be constructed to reward the worthy and slay those lacking.

In the 2013 D&D Championship, players needed to solve three puzzles to retrieve three magic staffs. The puzzles were created to prevent the addled, insane cultists of Zargon from seizing the staffs before worthy champions.

Dungeon Crawl Classics 15: Lost Tomb of the Sphinx Queen

In the Dungeon Crawl Classics adventure, Lost Tomb of the Sphinx Queen, the tomb is a prison for the evil Sphinx Queen. “The labyrinth below consists of a series of guardian creatures and traps, designed both to test the party (to ensure that they’re powerful enough to destroy Ankharet and her crown) and to teach them of the now-forgotten glories of the Sphinx Empire.”

The clues tempt intruders with false hopes for success

The dungeon includes clues and puzzles so that the any survivors who escape will spread tales that serve as a challenge, tempting more adventurers to test their meddle.

The original The Tomb of Horrors acts as trap to capture the souls of the strongest adventurers for some wicked purpose. The ambiguous clues written on the tomb’s floor seem almost as likely to lead to death as to success, so could they be a lure for more victims?

Challenges taunt intruders with the builder’s genius

The dungeon’s builder is like the serial killer who leaves clues because he wants to flaunt his genius over the cops pursuing him, or because his name is Edward Nigma so what else? This premise works as a more plausible version of the insane prankster.

The 2010, fourth edition Tomb of Horrors says, “It’s not enough for Acererak to win; he has to to prove his superiority by by saying, ‘I gave you a chance, and you still weren’t smart enough to beat me.’”

Someone wishes for the dungeon to fail its purpose

During a dungeon’s construction, something may have worked to sabotage it so that it ultimately fails its purpose. This sabotage can come from a few sources:

-

psychological conflict. We’ve all heard stories of the killer who secretly wished to be caught. Suppose a dungeon builder’s inner demons—or real, live demons—drive her to create a dungeon’s death traps, but her better nature, or some compulsion, or even a foe’s geas drives her to bury clues with the traps.

-

architects and workers. Most dungeon builders recruit architects and workers to construct their vaults. The patrons always boast of retirement plans, while they plan to slay their workers to preserve the dungeon’s secrets. But suppose the architects added clues as a means of revenge on their overlord? This results in a dungeon filled with clues subtle enough to escape the overlord’s notice, but within the grasp of clever adventurers.

Buyer beware: Charles IV of Spain and his Family paid for a portrait that flattered them with glittering jewels

and finery, but the family’s dead eyes reveal them as foolish and banal.

-

bargains. Fantasy includes many examples where bargains with mystical powers give a scheme an Achilles heel. Here, the dungeon’s weakness comes from the same, mighty powers called to help construction. Great magic often comes from a source with its own, unknowable motives.

In the Dungeon Crawl Classics adventure, Tears of the Genie, the Grand Caliph binds a djinni in his dungeon, but the gods of Àereth force the Grand Caliph hide the means of freeing the djinni within the prison.

Dungeon crawling is a sport

XCrawl

If adventurers crowd the streets and dungeons lie under every mountain, then dungeon crawling could become sport. This premise supports the six Challenge of Champions adventures that appeared in Dungeon magazine. Pandahead productions combined dungeon crawling for sport with all the posturing and pay-per-view rights of professional wrestling to create XCrawl. This premise abandons the mystery and enchantment of the exploring ruins, and replaces the thrill of confronting evil with artificial challenges and, in the case of XCrawl, humor.

If mortals can find sport in dungeons, then gods can too. Beedo from Dreams in the Lich House imagines death mountain, a place where the death god Hades can lure the land’s heroes, and then collect their skulls as trophies. This concept fits with the Olympians’ penchant for using mortal proxies as toys. “The other gods, for that matter, are greatly entertained when heroes overcome the machinations of the death god, and have gone so far as to sprinkle Hades’ sprawling dungeon with divine boons, godly weapons, and hidden shrines and sanctuaries where their beloved champions might gain a small respite.”

A religion or cult demands it

When Mike Shel decided to write an adventure inspired by Tomb of Horrors, he realized that the original tomb failed to provide much justification for its built-in clues and challenges. For The Mud Sorcerer’s Tomb, he created a cult of mud sorcerers, who “delighted in riddles and conundrums, disdaining those who couldn’t equal their mental prowess.” And then he gave them a reason for planting clues. “It may puzzle your players that Tzolo would leave hints lying about for would-be grave robbers. However, the clues were intended for for her liberating servants.”

Mike Shel was on to something. D&D’s assumed background needs a cult or religion that provides a ready-made excuse for dungeons that test characters with puzzles and strange obstacles. The mud sorcerers point the way, but their plan seems flawed. Why build clues for your servants that could also aid meddling do-gooders?

I propose a new creation.

The cult of Seermock, god of wealth and power through cunning

Seermock serves as a secret patron to those of wealth and power who earned their status through scheming and manipulation. Although few know of the cult’s existence, Seermock gladly spurns the common herd that he deems unworthy. Seermock upholds these principles:

- Wealth and power exist as a reward reserved for the cunning, while those of lesser intellect deserve impoverishment, servitude and then death.

- The weak minded who wish to claim wealth and power must suffer punishment for their presumption.

- Bequeathing wealth on the unworthy only rewards the foolish. Those cunning enough to join Seermock after death must strive to protect their worldly gains from those of dull wit.

Like many figures of wealth and power, followers of Seermock strive to memorialize their achievements with grand tombs. But followers of Seermock build their tombs to test those who attempt to seize the riches inside, rewarding the clever while slaying others presumptuous enough to seek treasures they do not deserve.